Residential School Survivors Made Lasting Mark in Sask. Sporting World

Sep 29

2023

By Matthew Gourlie via Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30th honours the children who never came home and the survivors of the residential school system as well as their families and communities.

The commemoration of the history and ongoing impact of the residential school system is an important part of the reconciliation process. The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation was established in response to Call to Action 80 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada which called for a federal statutory day of commemoration.

At the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame, we are committed to following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 87th Call to Action that calls on sports halls of fame to provide public education that tells the national story of Aboriginal athletes in history.

In that spirit, we are commemorating this National Day for Truth and Reconciliation by sharing some of the stories of inductees who had great athletic achievements despite what they suffered as children in the residential school system. We share them here as part of our learning and reflection on our shared history.

Fred Sasakamoose was born on Christmas Day, 1933 in the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation. When he was six years old, he and his brother Frank were taken from their parents by Indian agents from the Canadian government and driven with 30 other children to the St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake more than 100 kilometres away.

Sasakamoose wrote vividly and candidly about his experience at the residential school in his 2021 autobiography Call Me Indian: From the Trauma of Residential School to Becoming the NHL’s First Treaty Indigenous Player. He suffered horrible abuse at the school as well as dehumanizing treatment along with the other students.

Despite all that he suffered as a child, Sasakamoose excelled as a hockey player and reached the National Hockey League as a 19-year-old in 1953 with the Chicago Black Hawks. In doing so, Sasakamoose became the first Indigenous person with Treaty status to play in the NHL.

Before he reached the NHL, Sasakamoose starred as a junior player in Moose Jaw being named the Most Valuable Player in the Western Canadian Junior Hockey League in 1953-54. His junior career almost didn’t happen. Such was the pull of home after being taken from his family, Sasakamoose began walking the 400 kilometres back to Ahtahkakoop after two weeks in Moose Jaw before being convinced to stick it out and stay.

Sasakamoose would come home and spend 35 years as a Band Councillor of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation, six as Chief. He worked to give back to his community and build and develop minor hockey and other sports there.

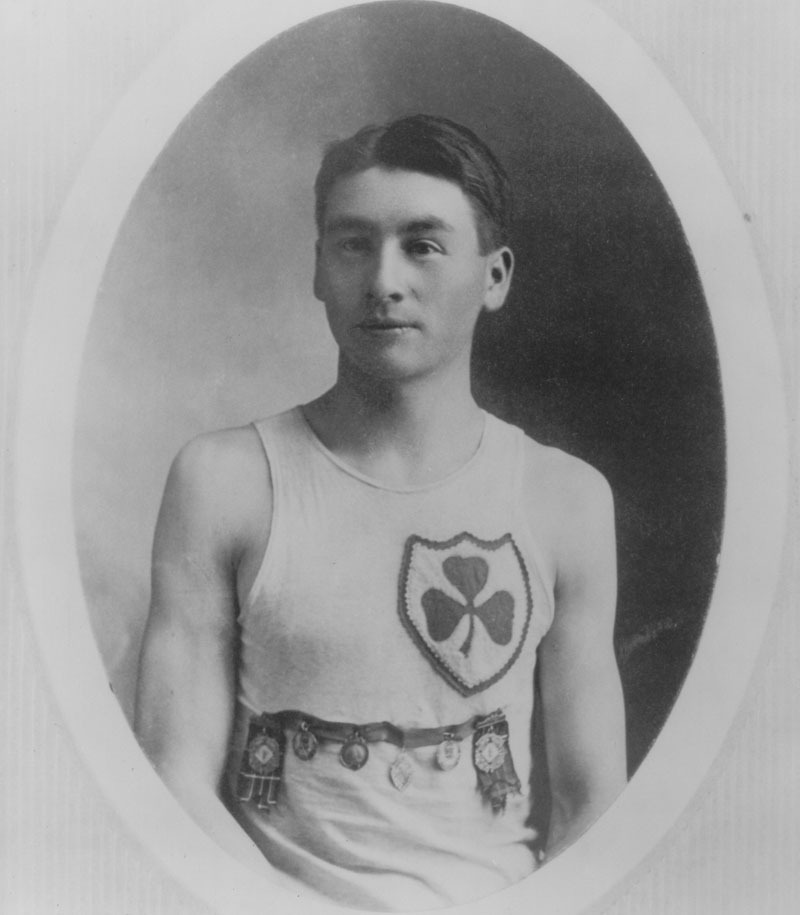

Alex Decoteau was born on the Red Pheasant First Nation in 1887 and was of Cree and Métis descent. His father Peter Decoteau fought beside Plains Cree Chief Pîhtokahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker) at the Battle of Cut Knife during the North-West Rebellion. Peter was an employee of the Indian Department when he was murdered. Alex was four years old at the time and he and his four siblings were sent to the Battleford Industrial School.

When it opened in 1883, the Battlefords Industrial School was the first residential school in Canada. Two more schools opened a year later and the Davin Report – which called for the “aggressive assimilation” of Indigenous children through the use and expansion of these new residential schools – was submitted to the Federal government.

After his time at the Battlefords Industrial School, Decoteau moved to Edmonton where he became the first Indigenous police officer in Canada in 1911. He was also a world-class distance runner. He became the first Saskatchewan athlete to compete at the Olympic Games when he ran the 5,000-metres in 1912.

He served in the 202nd Infantry Battalion and the 49th Battalion during the First World War and was killed during the Second Battle of Passchendaele in 1917.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame currently has 10 individual athletes who identify as Indigenous and have been inducted. Those athletes and builders are: Paul Acoose, Colette Bourgonje, Tony Cote, Alex Decoteau, David Greyeyes, Jacqueline Lavallee, Jim Neilson, Claude Petit, Fred Sasakamoose, and Bryan Trottier.

In addition to the individual Indigenous inductees, the SSHF also has inductees who were members of an inducted team.

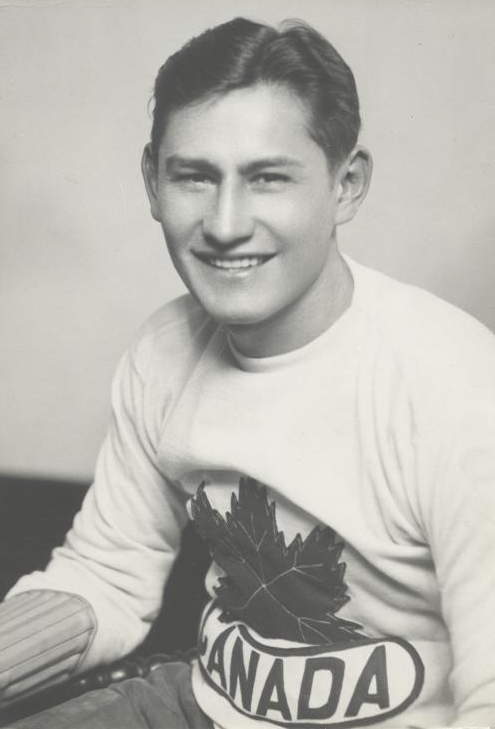

Kenneth Moore, from the Peepeekisis Cree Nation, was inducted into the SSHF as a member of the 1930 Regina Pats hockey team that won the Memorial Cup. Moore is also the first Indigenous athlete to win an Olympic gold medal.

Moore was born in 1910 as the third of eight siblings. His two older brothers had been taken to the Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba – more than 300 kilometres away. The two older Moore brothers died at the Brandon Indian Residential School with no details or cause provided to the family. Kenneth would have been forced to attend the school when he turned seven. Instead, the Moore family fled the Peepeekisis First Nation in the middle of the night.

The family settled in Regina, which was still more than 100 km from their home, but the younger Moore children were able to avoid the residential school system.

Ken Moore would star as a right winger on the Regina Pats junior hockey team. In 1930, the Pats met the West Toronto Nationals in the Memorial Cup final. Moore would score the game-winning goal with 40 seconds left which gave the Pats the series win and their third Memorial Cup in six years. He also attended Campion College and Regina College on a scholarship where he captained the hockey and rugby teams.

Moore later joined the Winnipeg Hockey Club and helped them claim the 1931 Allan Cup, the national amateur hockey championship. As Allan Cup champions, Winnipeg also earned the right to represent Canada at the 1932 Olympic Winter Games. Canada won five games and tied one to earn their fourth straight Olympic gold medal in hockey.

These stories from our inductees are just a small example of the countless ways the residential school system impacted the Indigenous population.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is proud to be physically located in Treaty 4 territory, which is home to the Cree, Dakota, Lakota, Nakota, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation. The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame also celebrates the history of sport and the people from the land that is covered by Treaties 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10. These lands have been the home of the Cree, Dakota, Dene, Lakota, Nakota, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame has a display case and video kiosk celebrating Saskatchewan Indigenous athletes and their achievements on permanent display in the Physical Activity Complex at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Kinesiology in Saskatoon.

Our nomination process is open to the public and if you believe you know of an athlete, builder or team that deserves inclusion in the Hall of Fame we invite you to nominate them. You can learn more about that process here.

Related Articles

Canada Takes Silver Medal at 2026 Olympic Winter Games

Hockey Saskatchewan MEMO: Application Open to Host 2027 Hockey Day in Saskatchewan

Ted Knight Sask. Hockey Hall of Fame Induction Dinner Comes to Moose Jaw with 2026 Class

Hudson Bay’s Kaiden Dyck Turns Devastating Injury into Senior Hockey Dream